Checklist of Centipedes in Mexican Amber

Lista anotada de ciempiés en ámbar mexicano

Cadenas-Amaya, Suzzet1,2![]() ; Riquelme, Francisco1,2,*

; Riquelme, Francisco1,2,*![]() ; Hernández-Patricio, Miguel3

; Hernández-Patricio, Miguel3![]() ; Cupul-Magaña, Fabio4

; Cupul-Magaña, Fabio4![]()

1 Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos, C.P. 62209, Cuernavaca, Morelos, México.

2 Maestría en Manejo de Recursos Naturales, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos, C.P. 62209, Cuernavaca, Morelos, México.

3 Unafiliate.

4 Centro Universitario de la Costa, Universidad de Guadalajara, C.P. 48280, Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco, Mexico.

* francisco.riquelme@uaem.mx

Abstract

Centipedes (Myriapoda: Chilopoda) are among the earliest terrestrial arthropods to have colonized the continents, with their fossil records dating back to the late Paleozoic. In Mexico, the fossil record of centipedes is exclusively found in the amber deposits of Chiapas, located in the southern region of the country. These deposits are estimated to have originated from the late Oligocene to the Early Miocene boundary, corresponding to a period of approximately 24 to 20 million years ago. We present an updated compilation of centipedes identified in Mexican amber. This report encompasses 22 amber inclusions, including 13 newly documented records across four orders, six families, and one genus. The order Geophilomorpha is the most represented, followed by Scolopendromorpha, Scutigeromorpha, and Lithobiomorpha. The new records belong to the families Henicopidae (Lithobiomorpha), Scutigeridae (Scutigeromorpha), and Schendylidae (Geophilomorpha). This inventory underscores the critical role of amber deposits in enhancing our understanding and documentation of Chilopoda diversity throughout geological history.

Keywords: Biodiversity, Chiapas, Chilopoda, Simojovel Formation, Simojovelite.

Resumen

Los ciempiés (Myriapoda: Chilopoda) se encuentran entre los primeros artrópodos terrestres que colonizaron los continentes, y su registro fósil se remontan al Paleozoico tardío. En México, el registro fósil de ciempiés se encuentra exclusivamente en los depósitos de ámbar de Chiapas, localizados en la región sur del país. Se estima que estos depósitos se originaron desde finales del Oligoceno hasta el límite del Mioceno Temprano, lo que corresponde a un período de aproximadamente 24 a 20 millones de años. Presentamos una compilación actualizada de ciempiés identificados en ámbar mexicano. Este informe abarca 22 inclusiones de ámbar, incluyendo 13 nuevos registros documentados en cuatro órdenes, seis familias y un género. El orden Geophilomorpha es el más representado, seguido por Scolopendromorpha, Scutigeromorpha y Lithobiomorpha. Los nuevos registros pertenecen a las familias Henicopidae (Lithobiomorpha), Scutigeridae (Scutigeromorpha), y Schendylidae (Geophilomorpha). Este inventario resalta el papel fundamental de los depósitos de ámbar para mejorar nuestra comprensión y documentación de la diversidad de Chilopoda a lo largo de la historia geológica.

Palabras clave: Biodiversidad, Chiapas, Chilopoda,Formación Simojovel, Simojovelita.

1. Introduction

Chilopoda represents one of the earliest animal taxa to inhabit terrestrial environments. Its evolutionary lineage can be traced back to the late Paleozoic (Edgecombe and Giribet, 2007), emphasizing its enduring presence and significance within terrestrial ecosystems. The oldest known fossils belong to the genus †Crussolum Shear, Jeram and Selden, 1998, which is part of the order Scutigeromorpha. †Crussolum was found in the Upper Silurian Ludlow Bone Bed Formation, England, dating back approximately 418 Ma (Shear et al., 1998).

In addition to Scutigeromorpha, the class Chilopoda includes four other orders: Lithobiomorpha, Scolopendromorpha, Geophilomorpha, and Craterostigmomorpha. Unlike Craterostigmomorpha, which is found only in Tasmania and New Zealand (Edgecombe, 2011), Scutigeromorpha, Lithobiomorpha, Scolopendromorpha, and Geophilomorpha are distributed worldwide. The global diversity of Chilopoda consists of five orders, 24 families, 339 genera, and 3110 extant species (Minelli, 2011a).

In Mexico, Chilopoda comprises four orders, 17 families, 75 genera, and 186 extant species (Cupul-Magaña, 2013; Cupul-Magaña and Flores-Guerrero, 2016; Bueno-Villegas and Cupul-Magaña, 2020). In contrast, the fossil record for Chilopoda includes three orders, three families, three genera, and one fossil species, all of which have been exclusively found in Oligo-Miocene Mexican amber (Edgecombe et al., 2012; Riquelme and Hernández-Patricio, 2018).

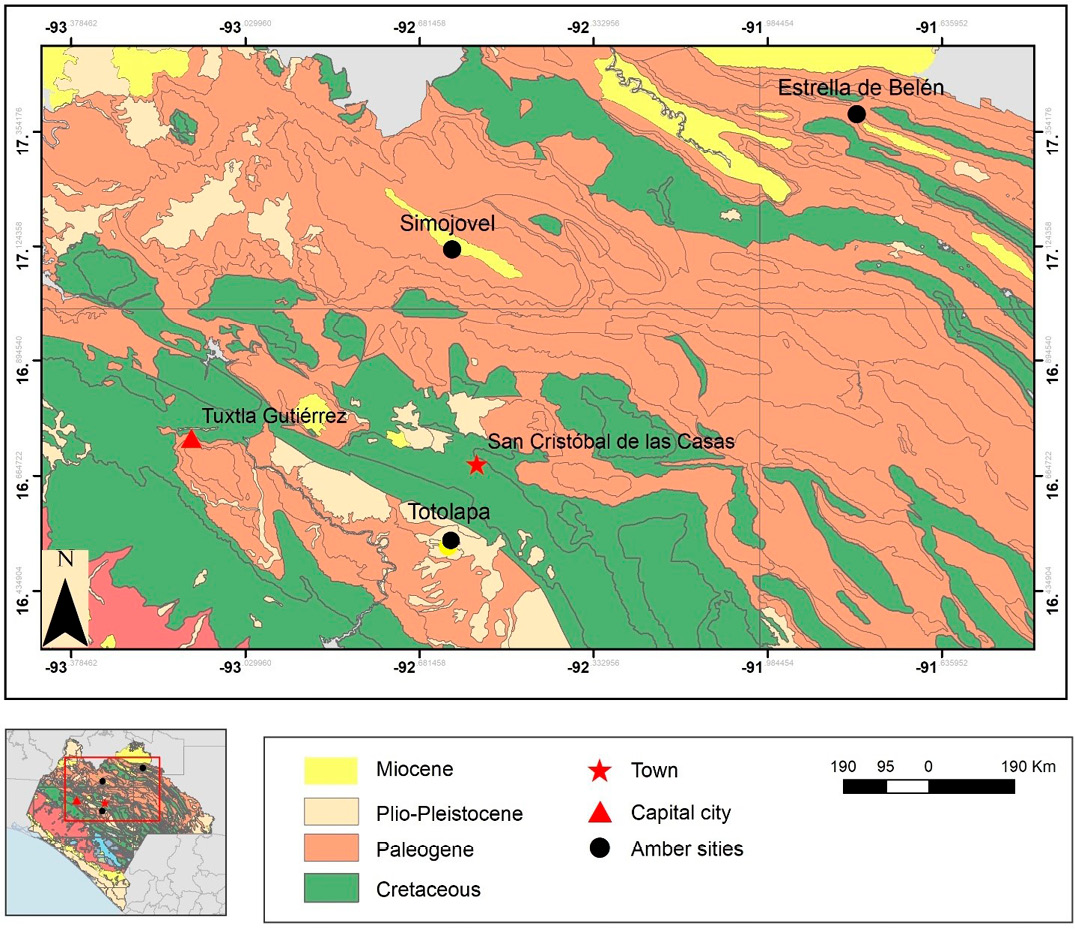

The present study provides an updated checklist of Chilopoda from amber sites in the Chiapas Highlands (Los Altos de Chiapas), southwestern Mexico (Figure 1). The fossil specimens listed in this inventory provide new material that supports prior records and introduces recent findings. This work contributes to the understanding of centipede diversity and their geographic distribution as represented in the fossil record.

2. Geological setting

The amber inclusions studied come from Simojovel, Totolapa, and Estrella de Belén deposits in Los Altos de Chiapas, Mexico (Figure 1). These three sites feature coeval sedimentary deposits and are part of the so-called Chiapas Amber Lagerstätte, which is chronologically positioned between the late Oligocene and the Early Miocene boundary, spanning an interval of approximately 24 to 20 Ma (Riquelme et al., 2025). Simojovel amber is derived from the uppermost section of the late Oligocene Simojovel Formation, whereas Totolapa amber originates from the Early Miocene Totolapa Sandstone, and Estrella de Belén amber is sourced from the uppermost section of the late Oligocene Mompuyil Formation. These amber strata mainly consist of limestones, siltstones, shales, fine-grained fossiliferous sandstones, lignite, iron oxides, and pyrite nodules (Riquelme et al., 2025).

The sedimentary record and paleobiota associated with the Simojovel Formation suggest that they were deposited in shallow environments and transitional coastal conditions, characterized by predominant estuary influences (Allison, 1967; Frost and Langenheim, 1974; Graham, 1999; Perrilliat et al., 2010; Riquelme et al., 2025). Amber sediments from Totolapa have also been associated with a mangrove environment that is similar to that of Simojovel (Durán-Ruiz et al., 2013; Breton et al., 2014; Castañeda-Posadas and Tomas-Mosso, 2024 ), as well as the Estrella de Belén (Riquelme et al., 2025).

The botanical origin of this amber is linked to an extinct leguminous tree from the genus Hymenaea Linné (sensu Langenheim, 1966). The amber displays chemical markers similar to those found in the resins of the living species Hymenaea courbaril Linné, 1753 and Hymenaea verrucosa Gaertner, 1791, which are commonly found in tropical regions (Langenheim, 2003). The mineral name of this amber is Simojovelite (Riquelme et al., 2014; 2025).

3. Material and methods

The fossil material studied is housed in the Colección Paleontológica, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos (CPAL-UAEM), Morelos, México. Supplementary material is housed at the Museo del Ámbar de Chiapas (MACH) and Museo del Ámbar Lilia Mijangos (MALM), both of which are located in San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas, México.

The taxonomic analysis of each fossil specimen was conducted using high-resolution microscopy with multiple image stacking (Z ≥ 45) on a Carl Zeiss microscope paired with an AXIO ZOOM V16 Axiocam MRc5 camera (5 megapixels). Photomicrographs were obtained at the Laboratorio de Microscopía y Fotografía de la Biodiversidad II del Laboratorio Nacional de la Biodiversidad (LaNaBio) del Instituto de Biología, UNAM, México City. Photomicrographs in the figures were processed and edited using Corel Draw® 2020 and Adobe Photoshop® 2020. The map was created using the Esri's ArcGIS 10.8 desktop GIS software. The checklist database can be found on the website www.riquelmelab.org.mx and is regularly updated. Anatomical terminology follows the standards established by Bonato et al. (2010). Nomenclature and taxonomic treatment are mainly based on Saussure and Humbert (1872), Cook (1896), Pocock (1898), Chamberlin (1912, 1943, 1960), Brolemann (1930), Eason (1964), Hoffman (1969, 1982), Lewis (1981), Mundel (1990), Adis (2002), Edgecombe and Giribet (2006), Bonato and Minelli (2010), and Minelli (2011b).

Repository abbreviations are as follows:

- AMNH—American Museum of Natural History, New York, USA.

- CPAL-UAEM—Colección de Paleontología, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos, Morelos, Mexico.

- MACH—Museo del Ámbar de Chiapas, San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas, Mexico.

- MALM—Museo del Ámbar Lilia Mijangos, San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas, Mexico.

- NMS—National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland.

4. Results

4.1. Systematic Paleontology

Phylum Arthropoda Gravenhorst, 1843

Clade Mandibulata sensu Snodgrass, 1938

Subphylum Myriapoda Latreille, 1802

Class Chilopoda Latreille, 1817

Subclass Notostigmophora Verhoeff, 1901

Order Scutigeromorpha Pocock, 1895

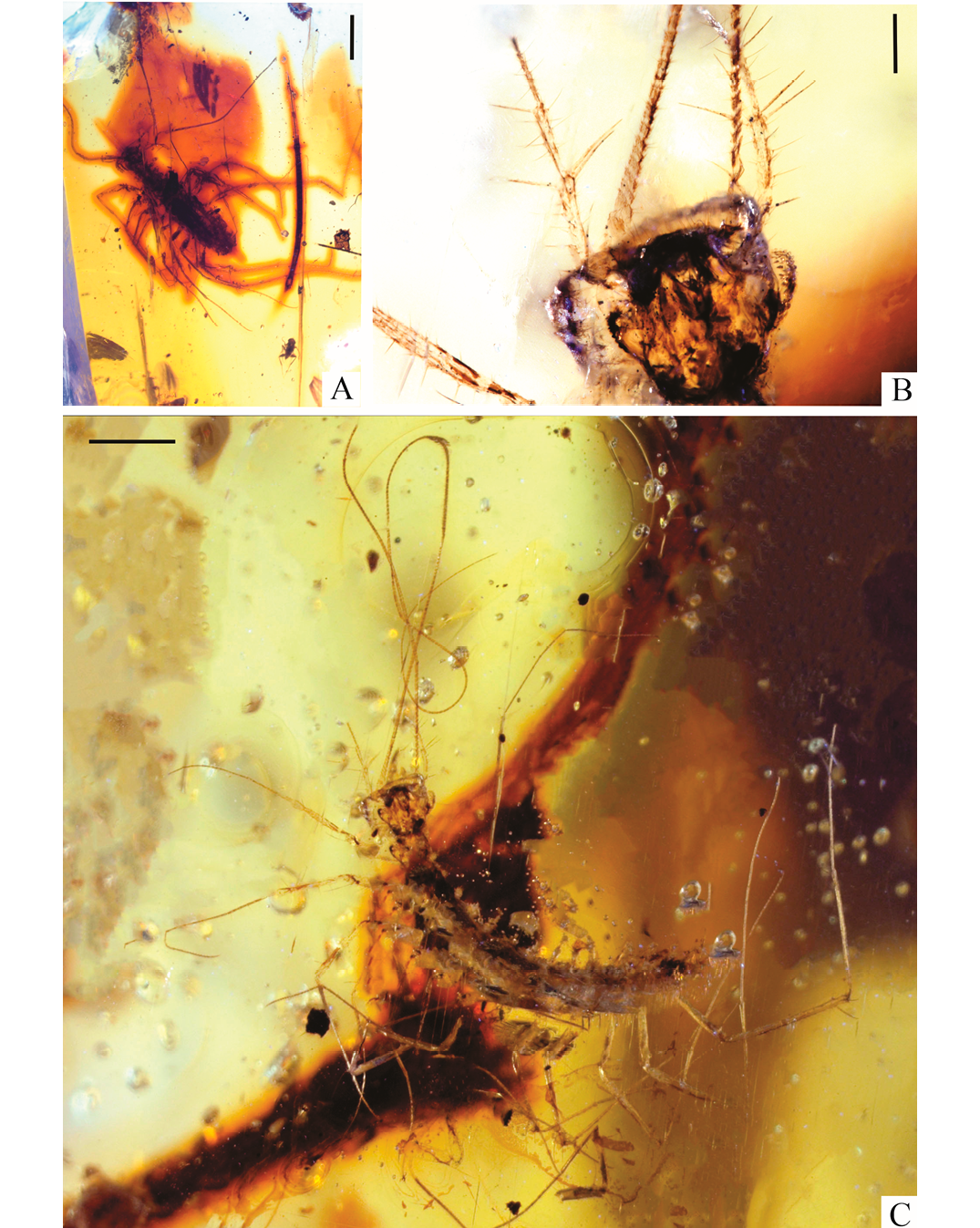

Scutigeromorpha indet.

Referred material. CPAL.192 amber inclusion (Table 1, Figure 2A).

Horizon and locality. Uppermost section of the Simojovel Formation, late Oligocene and Early Miocene boundary (ca. 24 Ma). México, Chiapas, Simojovel, Chapayal mine.

Description. The head capsule is approxi-mately hemispherical. The origin of the antenna is lateral rather than frontal; the rest of the antenna consists of the long flagellum made up of numerous annulations. The body is fusiform in shape and dorsoventrally flattened.

Family Scutigeridae Leach, 1814

Scutigeridae indet.

Referred material. CPAL.194 amber inclusion (Table 1, Figure 2B, C).

Horizon and locality. Uppermost section of the Simojovel Formation, late Oligocene and Early Miocene boundary (ca. 24 Ma). Mexico, Chiapas, Simojovel, Los Pocitos mine.

Description. The head has a large, convex shape. Presence of a transverse suture on the anterior part of the dorsal side of the head capsule. Antennal articles wider than long and eyes facetted. The body is composed of 15 leg-bearing segments. The legs are long.

Subclass Pleurostigmophora Verhoeff, 1901

Order Lithobiomorpha Pocock, 1895

Family Henicopidae Pocock, 1901

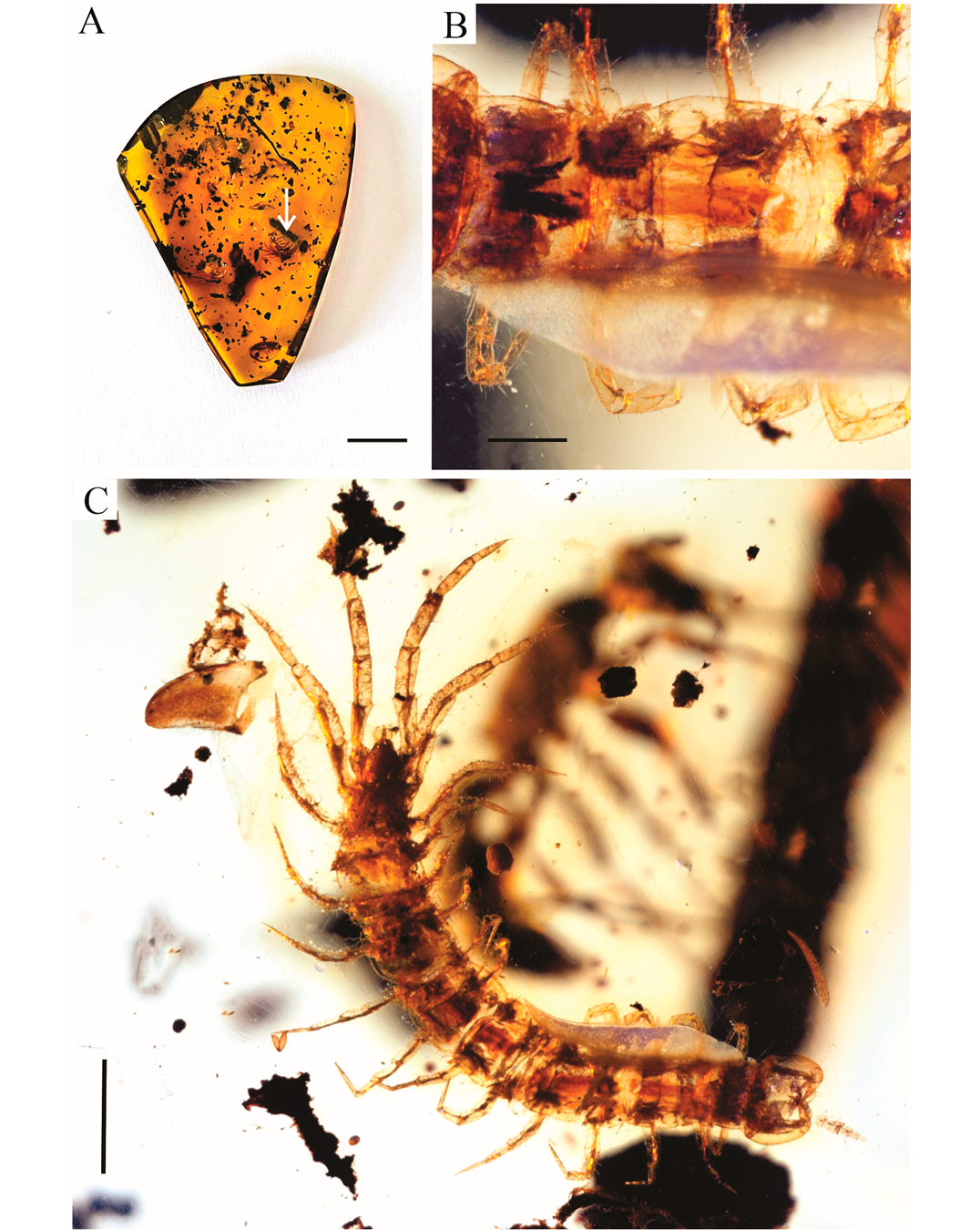

Henicopidae indet.

Referred material. CPAL.197 amber inclusion (Table 1, Figure 3).

Horizon and locality. Uppermost section of the Simojovel Formation, late Oligocene and Early Miocene boundary (ca. 24 Ma). Mexico, Chiapas, Simojovel, Monte Cristo mine.

Description. The head capsule is approxi-mately heart-shaped. A transverse suture crosses the anterior third of the head. The forcipular tergite is small. Marked heteronomy, tergites 2, 4, 6, 9, 11, and 13 being very much shorter than the others. The legs consist of a coxa, a telopodite with six segments, and an apical claw. Legs with no spines, but with setae.

Order Scolopendromorpha Pocock, 1895

Family Cryptopidae Kohlrausch, 1881

Cryptopidae indet.

Referred material. CPAL.160, CPAL.191, CPAL.204 amber inclusions (Table 1, Figure 4 A, B).

Horizon and locality. (CPAL.160) Uppermost section of the Mompuyil Formation, late Oligocene and Early Miocene boundary. Mexico, Chiapas, Estrella de Belén. (CPAL.191 and CPAL.204) uppermost section of the Simojovel Formation, late Oligocene and Early Miocene boundary (ca. 24 Ma). Mexico, Chiapas, Simojovel, Monte Cristo mine.

Description. Body flattened, moderately elongated. Antenna mostly attenuated gradually, with 17 articles. Eyes absent. The forcipular tergite is fused with the first trunk segment. Longitudinal paramedian sutures are present in the tergite. The number of pairs of legs is 21. The telopodite of the last pair of legs consists of five segments, the trochanter being absent.

Family Scolopocryptopidae Pocock, 1896

Scolopocryptopidae indet.

Referred material. CPAL.202 amber inclusion (Table 1, Figure 4C).

Horizon and locality. Uppermost section of the Simojovel Formation, late Oligocene and Early Miocene boundary (ca. 24 Ma). Mexico, Chiapas, Simojovel, Monte Cristo mine.

Description. Body flattened, moderately elongated. Antenna is mostly attenuated. Eyes absent. Forcipular tergite fused with the first trunk segment. Dorsoventrally compressed body composed of 23 segments and 23 pairs of legs including the terminals.

Order Geophilomorpha Pocock, 1895

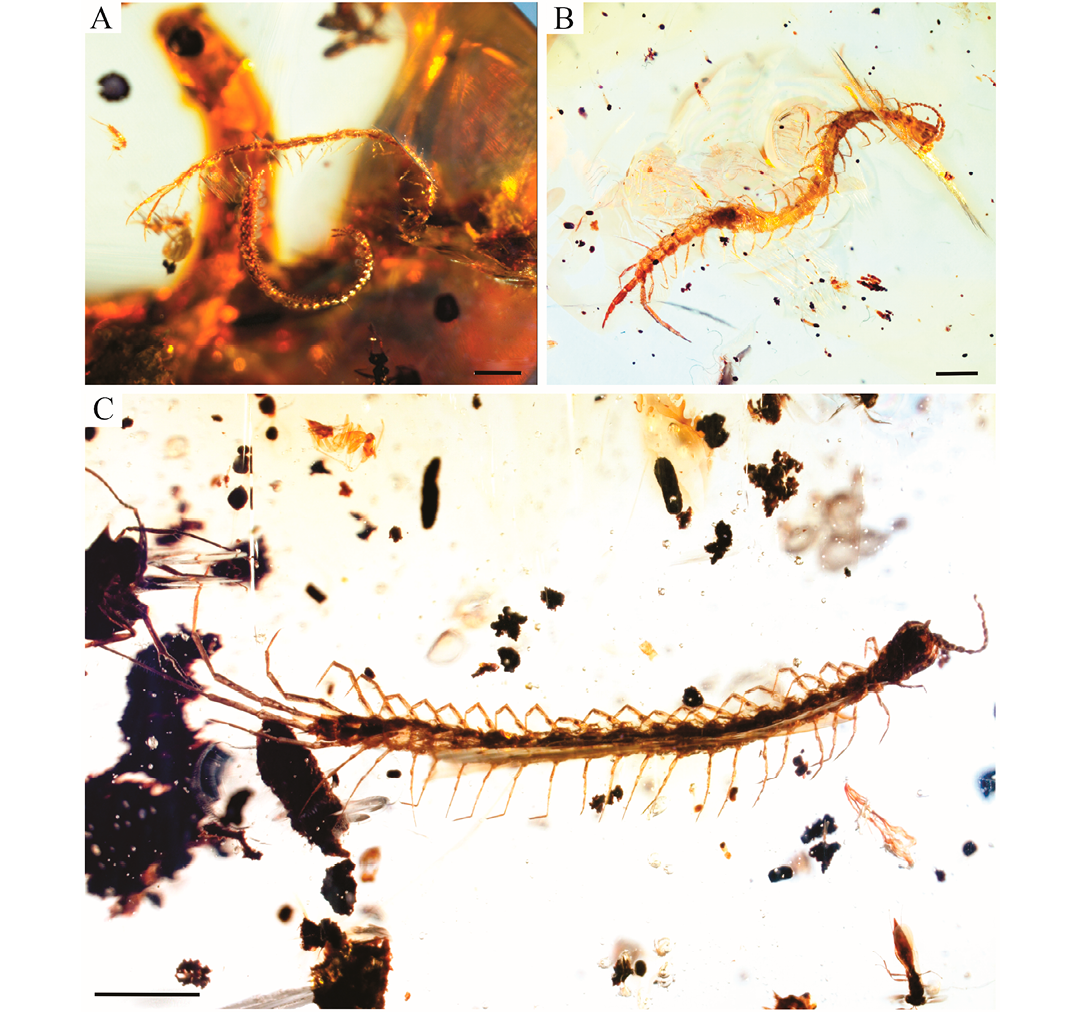

Geophilomorpha indet.

Referred material. CPAL.198 amber inclusion (Table 1, Figure 5A).

Horizon and locality. Uppermost section of the Simojovel Formation, late Oligocene and Early Miocene boundary (ca. 24 Ma). Mexico, Chiapas, Simojovel, Monte Cristo mine.

Description. Head capsule is elongated. Antennae long and filiform, with 14 segments. Eyes absent. Body slightly depressed, uniformly wide or gradually narrowing forwards, variously tapering backwards.

Family Geophilidae Leach, 1815

Genus Polycricus Saussure and Humbert, 1872

Polycricus sp.

Referred material. CPAL.196, CPAL.201 amber inclusions (Table 1, Figure 5B, C).

Horizon and locality. Uppermost section of the Simojovel Formation, late Oligocene and Early Miocene boundary (ca. 24 Ma). Mexico, Chiapas, Simojovel, Los Pocitos mine (CPAL.196); Monte Cristo mine (CPAL.201).

Description. Body slightly depressed. Elongate cephalic plate, quadrate and elongate with rounded corners and lacks ocelli. Antennae long and filiform, divided by 14 articles. Antennae two or three times longer than the head and very close to the base. Forcipular segment elongate and broad, forcipules formed by four segments, with the presence of a basal denticle on the tarsungulum. Sternal pores present.

Family Shendylidae Cook, 1896

Schendylidae indet.

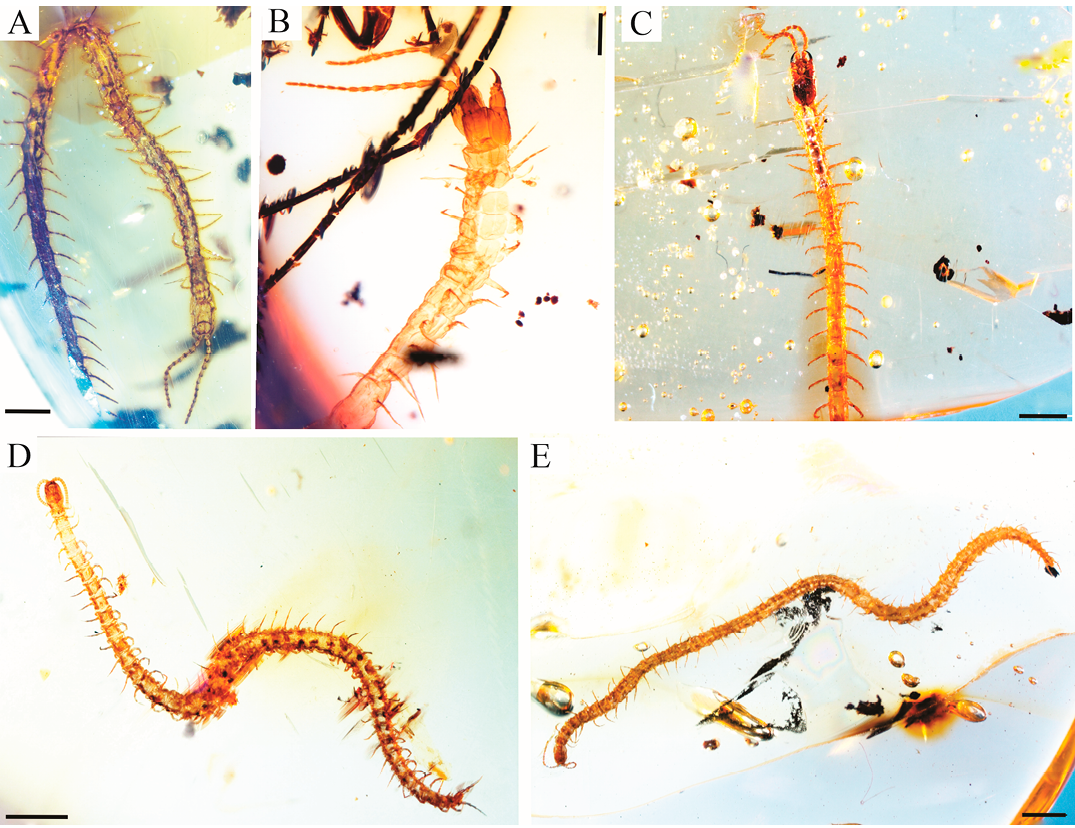

Referred material. CPAL.147, CPAL.148, CPAL.203 amber inclusions (Table 1, Figure 5D, E).

Horizon and locality. (CPAL.147) Totolapa Sandstone (Early Miocene); Mexico, Chiapas, Totolapa, Río Salado. Uppermost section of the Simojovel Formation, late Oligocene and Miocene boundary (ca. 24 Ma); Mexico, Chiapas, Simojovel, Los Pocitos mine (CPAL.148), Monte Cristo mine (CPAL.203).

Description. Body slender, gradually tapering towards the posterior tip. Head somewhat elongate, antennae long and filiform. Antennae divided by 14 antennal articles. Cephalic lamina not concealing the prehensors, forcipular pretergite evident or concealed. Forcipules formed by four segments, forcipular segment broad, tergite subtrapezoid and narrower than the subsequent tergite, forcipules relatively large and close to each other. The number of legs bearing segments varies within each morphotype, ranging from 45 (CPAL, 147 and 148) to 43 (CPAL.203). The ultimate leg is composed of five (CPAL.147) or six segments (CPAL.148 and CPAL.203) and has an apical spine. Sternal porefields present.

5. Discussion

The depositional environment of Mexican amber indicates that it is representative of an estuarine ecosystem (Frost and Langenheim, 1974; Perrilliat et al., 2010; Riquelme et al., 2025). Palaeobotanical data suggest a tropical forest habitat (Graham, 1999; Langenheim, 2003; Hernández-Hernández et al., 2020), Castañeda-Posadas and Tomas-Mosso, 2024). Accordingly, the centipedes studied align with the biota of a tropical forest close to the coastal plain.

In the studied fossil assemblage examined, we observe a greater number of geophilomorph centipedes, taking into account the sample bias (Table 1). We also noted this trend in fieldwork, encountering additional geophilomorph specimens that were not included in our assemblage because they were in private collections. The higher number of geophilomorph centipedes observed does not directly indicate greater species richness compared to other groups. Rather, it is likely a result of taphonomic processes (Martínez-Delclòs et al., 2004). Geophilomorph centipedes consist of soil-dwelling species that exhibit adaptations for burrowing. As a result, they were more likely to become trapped in resin as it was deposited on the soil and flowed down the trunks and branches of Hymenaea trees. Therefore, resin encapsulation is expected to occur more often in soil.

The fossil record for Geophilomorpha, Scolopendromorpha, and Scutigeromorpha, is documented in Paleozoic and Mesozoic deposits (Shear and Edgecombe, 2010 ; Edgecombe, 2011), while Lithobiomorpha is primarily found in Cenozoic strata (Table 2), particularly within Eocene amber from the Baltic region (Koch and Berendt, 1854; Edgecombe, 2011). We are documenting a new record for Lithobiomorpha in Mexican amber. Previously, Hurd et al. (1962) noted the presence of the family Henicopidae (Lithobiomorpha) in Mexican amber. However, this observation lacks comprehensive specimen data. It does not include descriptions, provenance information (mine or locality), repository details, or accompanying specimen images. The fossil specimen is likely to have been lost. Consequently, this tentative report is considered questionable.

The case above underscores the inconsistency found in reports and collections of fossil material, particularly regarding amber inclusions from Mexico. The trade of Mexican fossil material has significantly hindered research opportunities, adversely affecting our comprehension of ancient biodiversity. To address this challenge, we have a conservation initiative that utilizes taxonomic inventories as the first step toward preserving amber inclusions within curated material and repositories located in Mexico, as proposed in Riquelme and Hernández-Patricio (2018).

6. Conclusions

Prior to this study, the knowledge of the centipede fossil record in Mexico was limited to nine amber inclusions. In comparison, more extensive collections have been identified in other Cenozoic geological deposits, such as the late Eocene Baltic amber and Early Miocene Dominican amber (Table 2). We have reported 13 new records for Mexican amber, comprising four orders: Geophilomorpha, Scolopendromorpha, Scutigeromorpha, and Lithobiomorpha, six families: Scutigeridae, Henicopidae, Cryptopidae, Scolopocryptopidae, Geophilidae, and Schendylidae, and the genus Polycricus. For the first time, we have documented the family Scutigeridae within Scutigeromorpha, the family Schendylidae within Geophilomorpha, and the family Henicopidae within Lithobiomorpha (Table 1). Terrestrial arthropods, including centipedes, found in Oligo-Miocene Mexican amber generally correlate with the living species distributed in the modern Neotropical and Nearctic regions, which share taxonomic affinities. Thus, this inventory enhances our understanding of centipede diversity in the southernmost region of North America.

Acknowledgments

The SECIHTI grant supported SCA as part of the MMRN postgraduate program at the UAEM. We thank Luis Zúñiga for access to the MALM collection and Bibiano Luna for the

MACH collection. We also thank Susana Guzmán-Gómez at the LMF2-LANABIO, Instituto de Biología-UNAM, for photomicrography assistance. We also thank the Editor-in-Chief, Josep A. Moreno Bedmar, and the anonymous reviewers for their invaluable comments and corrections, which enhanced the final published paper. We thank Sandra Ramos, León Felipe Álvarez, and the editorial team for their assistance with editing and proofreading.

Authors' Contribution

Conceptualization: FR, SCA

Data curation: SCA, FR

Formal analysis: FR, SCA

Funding acquisition: FR

Investigation: SCA, FR

Methodology: FR, SCA

Validation: FR, SCA, MHP, FCM

Visualization: FR, SCA, MHP, FCM

Writing – original draft: FR, SCA

Writing – review & editing: FR, SCA, MHP, FCM.

Competing interests

The authors declare there are no competing interests.

References

Adis, J. (2002). Myriapoda: identification to classes. In J. Adis (Ed.), Amazonian Arachnida and Myriapoda: Identification keys to all classes, orders, families, some genera, and lists of known terrestrial species (pp. 457–501). Pensoft.

Allison, R. C. (1967). The Cenozoic stratigraphy of Chiapas, Mexico, with discussions of the classification of the Turritellidae and selected Mexican representatives [Unpublished PhD tesis]. University of California at Berkley.

Bachofen-Echt, A. (1942). Über die Myriapoden des Bernsteins. Palaeobiologica, 7, 394– 403.

Bonato, L., & Minelli, A. (2010). The Geophilomorph centipedes of the Seychelles (Chilopoda: Geophilomorpha). Phelsuma, 18, 9–38.

Bonato, L., Edgecombe, G. D., Lewis, J. G., Minelli, A., Pereira, L. A., Shelley, R. M., & Zapparoli, M. (2010). A common terminology for the external anatomy of centipedes (Chilopoda). ZooKeys, 69, 17–51. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.69.737

Brolemann, H. W. (1930). Eléments d'une faune des Myriapodes de France: Chilopodes. Imprimerie Toulousaine.

Breton, G., Serrano-Sánchez, M. L., & Vega, F. J. (2014). Filamentous microorganisms, inorganic inclusions and pseudo-fossils in the Miocene amber from Totolapa (Chiapas, Mexico): taphonomy and systematics. Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, 66(1), 199–214. doi:10.18268/BSGM2014v66n1a14.

Bueno-Villegas, J., & Cupul-Magaña, F. G. (2020). Actualización del Catálogo de Autoridades Taxonómicas (CAT) de Myriapoda en México. Universidad de Guadalajara, Centro Universitario de la Costa. Informe final SNIB-CONABIO, Proyecto No. KT009. Ciudad de México.

Chamberlin, R. V. (1912). The Chilopoda of California III. Pomona College Journal of Entomology, 4(1), 651–672.

Chamberlin, R. V. (1943). On Mexican centipedes. Bulletin of the University of Utah, Biological Series, 7, 1–55. https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6b85sxw

Chamberlin, R. V. (1949). A new fossil centipede from the Late Cretaceous. Transactions of the San Diego Society of Natural History, 11, 117–120.

Chamberlin, R. V. (1960). A new marine centiped from the California littoral. Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington, 73, 99–101.

Castañeda-Posadas, C., & Tomas-Mosso, A. (2024). Estudio palinológico de una sección portadora del ámbar de Totolapa, en Chiapas, México. Paleontología Mexicana, 13(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.22201/igl.05437652e.2024.13.1.368

Cook, O. F. (1896). An arrangement of the Geophilidae, a family of Chilopoda. Proceedings of the United States National Museum, 18(1039), 63–75.

Cupul-Magaña, F. G. (2013). Chilopoda: La diversidad de los ciempiés (Chilopoda) de México. Dugesiana, 20(1), 17–41. https://doi.org/10.32870/dugesiana.v20i1.4076

Cupul-Magaña, F. G., & Flores-Guerrero, U. S. (2016). Guía para la determinación de las familias de ciempiés (Myriapoda: Chilopoda) de México: Una actualización. Revista Bio Ciencias, 4(1), 40–51. https://doi.org/10.15741/revbio.04.01.04

Durán-Ruiz, C., Riquelme, F., Coutiño-José, M., Carbot-Chanona, G., Castaño-Meneses, G., & Ramos-Arias, M. (2013). Ants from the Miocene Totolapa amber (Chiapas, Mexico), with the first record of the genus Forelius (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 50(5), 495–502.

Dunlop, J. A., Friederichs, A., & Langermann, J. (2017). A catalogue of the Scutigeromorph centipedes in the Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin. Zoosystematics and Evolution, 93(2), 281–295. https://doi.org/10.3897/zse.93.12882

Eason, E. H. (1964). Centipedes of the British Isles. Frederick Warne & Co.

Edgecombe, G. D. (2011). Chilopoda-Taxonomic Overview Order Scutigeromorpha. In A. Minelli (Ed.), The Myriapoda (Treatise on Zoology-Anatomy, Taxonomy, Biology) (vol.1, pp. 363–370). Brill.

Edgecombe, G. D., & Giribet, G. (2006). A century later–a total evidence re-evaluation of the phylogeny of scutigeromorph centipedes (Myriapoda: Chilopoda). Invertebrate Systematics, 20(5), 503–525.

Edgecombe, G. D., & Giribet, G. (2007). Evolutionary biology of centipedes (Myriapoda: Chilopoda). Annual Review of Entomology, 52, 151–170. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ento.52.110405.091326

Edgecombe, G. D., Vahtera, V., Stock, S. R., Kallonen, A., Xiao, X., Rack, A., & Giribet, G. (2012). A scolopocryptopid centipede (Chilopoda: Scolopendromorpha) from Mexican amber: synchrotron microtomography and phylogenetic placement using a combined morphological and molecular data set. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 166(4), 768–786. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.2012.00860.x

Frost, S., & Langenheim, Jr. R. (1974). Cenozoic reef biofacies, Tertiary larger foraminifera and Scleractinian corals from Chiapas, Mexico. Northern Illinois. University Press, De Kalb.

Gaertner, J. (1791). De Fructibus et Seminibus Plantarum. Typis Academiae Carolinae, Stuttgart.

Graham, A. (1999). Studies in neotropical paleobotany. XIII. An Oligo-Miocene Palynoflora from Simojovel (Chiapas, México). American Journal of Botany, 86(1), 17–31. https://doi.org/10.2307/2656951

Gravenhorst, J. L. C. (1843). Vergleichende Zoologie. Breslau.

Haug, J. T., Müller, C. H., & Sombke, A. (2013). A centipede nymph in Baltic amber and a new approach to document amber fossils. Organisms Diversity & Evolution, 13, 425–432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13127-013-0129-3

Hernández-Hernández, M. J., Cruz, J. A., & Castañeda-Posadas, C. (2020). Paleoclimatic and vegetation reconstruction of the Miocene Southern Mexico using fossil flowers. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 104(102827), 1–8. https://doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2020.102827

Hoffman, R. L. (1969). Myriapoda, Exclusive of Insecta. In R.C. Moore (Ed.), Arthropoda 4. (Treatise on invertebrate paleontology, part R) (vol. 2, pp. R598–R604). The Geological Society of America and University of Kansas Press.

Hoffman, R. L. (1982). Chilopoda. In S. P. Parker, (Ed.), Synopsis and classification of living organisms (pp. 681–689). McGraw-Hill.

Hurd, P. D., Smith, R. F., & Durham, J. W. (1962). The fossiliferous amber of Chiapas, México. Ciencia, 21, 107–118.

Koch, C. L., & Berendt, G. C. (1854). Die im Bernstein befindlichen Crustaceen, Myriapoden, Arachniden und Apteren der Vorwelt. Die in Bernstein Befindlichen Organischen Reste der Vorwelt Gesammelt in Verbindung mit Mehreren Bearbeitetet und Herausgegeben. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/42425998

Kohlrausch, E. (1881). Gattungen und Arten der Scolopendriden. Archiv für Naturgeschichte, 47(1), 50–132.

Langenheim, J. H. (1966). Botanical source of amber from Chiapas, Mexico (Fuente botánica del ámbar de Chiapas, México). Ciencia, 24(5–6), 201–210.

Langenheim, J. H. (2003). Plant Resins: Chemistry, Evolution, Ecology, and Ethnobotany. Timber Press.

Latreille, P. A. (1802). Histoire naturelle, générale et particulière des Crustacés et des Insectes. Dufart.

Latreille, P. A. (1817) Les crustacés, les arachnides et les insectes, In G. Cuvier (Ed.), Le Règne animal distribué d'après son organisation, pour servir de base à l'histoire naturelle des animaux et d'introduction à l'anatomie compare (1era ed., pp.148–158). Déterville.

Leach W. E. (1814). Crustaceology, In D. Brewster (Ed.), The Edinburgh Encyclopaedia (vol. 7, pp. 383–437). Edinburgh, Blackwood.

Leach, W. E. (1815). A tabular view of the external characters of four classes of animals, which Linné arranged under Insecta; with the distribution of the genera composing three of these classes into orders, and descriptions of several new genera and species. Transactions of the Linnean Society of London, 11, 306–400.

Lewis, J. G. E. (1981). The biology of centipedes. Cambridge University Press.

Linné, C. (1753). Species plantarum. Laurentii Salvii.

Martı́nez-Delclòs, X., Briggs, D. E., & Peñalver, E. (2004). Taphonomy of insects in carbonates and amber. Palaeogeography, palaeoclimatology, palaeoecology, 203(1–2), 19–64.

Menge, A. (1854). Footnote. In C. L. Koch & G. C. Berendt (Eds.), Die im Bernstein Befindlichen Crustaceen, Myriapoden, Arachniden, und Apteren der Vorwelt (pp. 18–19). Nicolaischen Buchhandlung.

Minelli, A. (2011a). Class Chilopoda, Class Symphyla and Class Pauropoda. In Z. Q. Zhang (Ed.), Animal biodiversity: An outline of higher–level classification and survey of taxonomic richness. Zootaxa, 3148(1), 1–237. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3148.1.31

Minelli, A. (2011b). Treatise on Zoology - Anatomy, Taxonomy, Biology The Myriapoda. Brill.

Mundel, P. (1990). Chilopoda. In D. L. Dindal (Ed.), Soil Biology Guide (pp. 819–833). John Wiley & Sons: Brisbane.

Peñalver, E., Delclòs Martínez, X., & Serra, A. (1997). Hallazgo del género Lithobius (Chilopoda, Lithobiomorpha) en registro fósil del Mioceno de Rubielos Mora. In J. P. Calvo, & J. Morales (Eds.), Avances en el conocimiento del Terciario Ibérico (pp. 153–155).

Perrilliat, M., Vega, F., & Coutiño, M. (2010). Miocene mollusks from the Simojovel area in Chiapas, southwestern Mexico. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 30(2), 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2010.04.005

Pocock, R. I. (1895-1896). Chilopoda. In F. D. Godman & O. Salvin (Eds.), Biologia Centrali-Americana (vol. 14, pp. 1–40). Porter

Pocock, R. I. (1898). Report on the centipedes and millipedes obtained by Dr. A. Willey in the Loyalty Islands, New Britain, and elsewhere. In A. Willey (Ed.), Zoological results based on material from New Britain, New Guinea, Loyalty Isles and elsewhere (vol. 1, pp. 59–74). University Press, Cambridge.

Pocock, R. I. (1901). Some new genera and species of Lithobiomorphous Chilopoda. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 7(8), 448–451.

Poinar, G. Jr., & Poinar, R. (1999). The Amber Forest: A Reconstruction of a Vanished World. Princeton University Press.

Poinar, G. O. (1992). Life in amber. Stanford University Press.

Riquelme, F., Ruvalcaba-Sil, J. L., Alvarado-Ortega, J., Estrada-Ruiz, E., Galicia-Chávez, M., Porras-Múzquiz, H., & Miller, L. (2014). Amber from México: Coahuilite, Simojovelite and Bacalite. MRS Online Proceedings Library (OPL), 1618, 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1557/opl.2014.466

Riquelme, F., & Hernández-Patricio, M. (2018). The millipedes and centipedes of Chiapas amber. Check List, 14(4), 637–646. https://doi.org/10.15560/14.4.637

Riquelme, F., Ortega-Flores, B., Estrada-Ruiz, E., & Córdova-Tabares, V. (2025). Zircon U-Pb Ages of the Chiapas Amber-Lagerstätte in the Uppermost Simojovel Formation, Southeastern Mexico. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjes-2024-0100

Ross, A., & Sheridan, A. (2013). Amazing Amber. NMS Enterprises Limited-Publishing

Ross, A. J., Mellish, C. J., Crighton, B., & York, P. V. (2016). A catalogue of the collections of Mexican amber at the Natural History Museum, London, and National Museums Scotland, Edinburgh, UK. Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, 68(1), 45–55. https://doi.org/10.18268/BSGM2016v68n1a7

Saussure de H., & Humbert, A. (1872). Études sur les myriapodes. In H. Milne-Edwards (Ed.), Mission scientifique au Mexique et dans l'Amérique Centrale Recherches zoologiques (pp. 139–211). Mémoires du Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle.

Shear, W. A. (1987). Myriapod fossils from the Dominican Amber. In 7th International Congress of Myriapodology. Vittorio Veneto Italia, ed. A. Minelli, 43.

Shear, W. A., Jeram, A. J., & Selden, P. A. (1998). Centiped legs (Arthropoda, Chilopoda, Scutigeromorpha) from the Silurian and Devonian of Britain and the Devonian of North America. American Museum Novitates, 3231, 1-16.

Shear, W. A., & Edgecombe, G. D. (2010). The geological record and phylogeny of the Myriapoda. Arthropod Structure & Development, 39(2–3), 174–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asd.2009.11.002

Snodgrass, R. E. (1938). Evolution of the Annelida, Onychophora and Arthropoda. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, 97(6), 1–159.

Verhoeff, K. W. (1901). Beiträge zur Kenntnis paläarktischer Myriopoden. XVI. Aufsatz: zur vergleichenden Morphologie, Systematik und Geographie der Chilopoden. Abhandlungen der Kaiserlichen Leopoldinisch-Carolinisch Deutschen Akademie der Naturforscher, Nova Acta, 77, 369–465.

Weitschatt, W., & Wichard, W. (1998). Atlas of plants and animals in Baltic amber. Pfeil, München.

Wu, R. J. C. (1997). Secrets of a Lost World: Dominican amber and its Inclusions. Self-published.